Problem and hypothesis

Soft law seems to somehow accommodate two characteristics: it does not have a legally binding nature – or legally binding force, legally binding effects, or simply ‘bindingness’ – yet at the same time it does have some other legal effects. It is not readily apparent how it is possible for a measure that has legal effects not to be legally binding. This raises the question of what exactly is meant by the notions of ‘(legally) binding effect’ and ‘legal effect’. Exploring the former leads to the application of a binary approach: a given rule of conduct is either binding and belongs to the realm of hard law, or it lacks legally binding force and belongs to the category of soft law. The relevant criterion for ascribing a measure to one category or the other is, therefore, its binding nature, which turns the notions of hard and soft law into binary concepts with a classifying function.

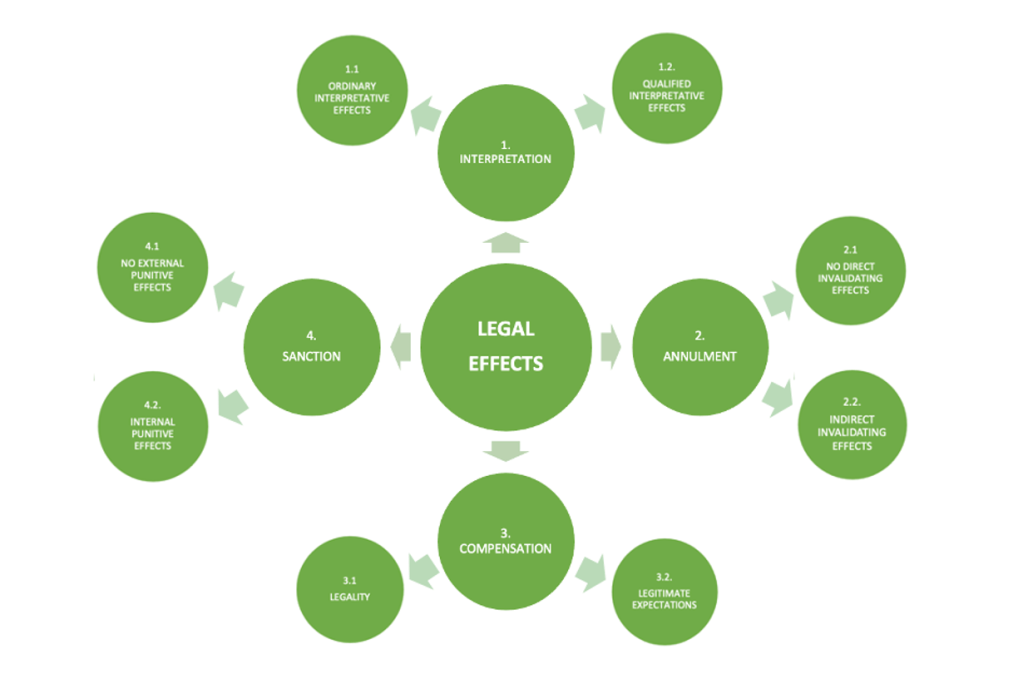

The perspective provided by this criterion is valuable: it allows us to assess the impact of a rule on other components of the system of legal sources. By focusing exclusively on its legally binding effects, however, it contributes to concealing the fact that EU soft law measures, even though they do not have a legally binding nature, may have various other legal effects. The hypothesis the chapter published in ‘The legal effects of EU soft law’ (Edward Elgar, 2023, edited by Petra Lea Láncos, Napoleon Xanthoulis and Luis Arroyo Jiménez) this blog piece is based on is that ‘binding effects’ or ‘legally binding effects’ – i.e., the legal effects of an act resulting from its legally binding nature – are a particular type of ‘legal effects’. Consequently, there are other legal effects that are not covered by the notion of ‘bindingness’ which can be classified into four categories: interpretative effects, indirect invalidating effects, compensatory effects, and indirect punitive effects.

Interpretative effects

EU soft law has ordinary interpretative effects since it can provide arguments and lines of reasoning for the interpretation of the hard law provisions to which it relates, namely: (i) genetic arguments relating to the author’s purpose, if the soft law measure was adopted by the same authority that enacted the hard law rule that is at issue; (ii) arguments relating to the objective meaning of the hard law rule, if the soft law measure reflects how other actors understood, or actually understand the meaning of the former; and (iii) systematic arguments, if they contribute to clarifying how the hard law rule relates to other sources of law.

However, in certain cases, hard law may grant qualified interpretative effects upon soft law measures. Here, soft law imposes legal obligations or conditions on the judicial or administrative authorities responsible for interpreting hard law. A first type of qualified interpretative effect arises when administrative or judicial authorities are legally obliged to take into account soft law acts – or some types thereof – when interpreting hard law rules. In this case, soft law would be a mandatory interpretation aid. A second type of qualified interpretative effect would go one step further by imposing a legal obligation on administrative or judicial authorities to interpret hard law as far as possible in a manner consistent with soft law. This is not simply a matter of taking the latter into account, but of interpreting the hard rule in conformity with the soft law measure. In this case, soft law would benefit from a duty of consistent interpretation. While Grimaldi and its progeny are slowly expanding the first type of qualified interpretative effect, the second one is not to be found in EU soft law – and rightly so.

Indirect invalidating effects

Compliance with the rules of conduct established by EU soft law instruments is not, in and of itself, a condition for the validity of subsequent rules or acts. Therefore, EU soft law cannot logically have direct invalidating effects. This is not an accidental feature of the position enjoyed by soft law in a given legal order, but a logical feature of the concept thus conceived. Accordingly, if a court grants direct invalidating effects upon a rule, it will no longer qualify as soft law. This is how the Court of Justice’s doctrine on incidental binding force must be understood.

There are, however, three groups of cases in which non-compliance with EU soft law can have indirect invalidating effects. Here, subsequent acts which deviate from the rules of conduct enshrined in an EU soft law measure are unlawful. However, such invalidating effects are ‘indirect’ because the ground of illegality is not the breach of EU soft law, but other hard law rules or principles, that are triggered by the breach of EU soft law. Moreover, in some of these cases, the breach of EU soft law is a necessary, but not sufficient, condition for invalidity, as hard law may lay down additional requirements for the subsequent act to be illegal, over and above the infringement of soft law. The first group of cases concerns EU soft law measures backed by binding – EU or national – hard law rules or decisions, which may either reproduce them or incorporate them by reference. In the second group, EU law lays down a hard law rule that imposes a burden on national authorities who decide not to abide by EU soft law – the duty to take into consideration, the duty to take the utmost account, the duty to comply-or-explain, and so on. In the third group of cases, non-compliance with EU soft law would be one of the conditions triggering indirect invalidating effects under a general principle of law, namely, equality, legitimate expectations, and, admittedly more controversially, sincere cooperation.

Compensatory effects

Disregard of EU soft law by an EU or a national authority could also give rise to compensation claims in two groups of cases. In the first one, the ground for compensation is illegality. However, illegality does not always give rise to compensation for the injured parties. Compensation is not coextensive with annulment under EU law because the Court of Justice only recognises a right to compensation if three conditions are met: (i) the existence of a sufficiently serious breach of a rule of law intended to confer rights on individuals; (ii) the fact of damage; and (iii) the existence of a causal link between the breach of the rule and the damage suffered by the injured parties.

These conditions make it very difficult to award damages based on the indirect invalidating effects of EU soft law. First, it will be necessary to show that the disregard of the soft law instrument implies that a hard law rule or principle that intended to confer individual rights has also been infringed. And typically, this won’t be the case (i) of the infringement of soft law measures on administrative organisation, cooperation and procedure, (ii) of indirect invalidating effects triggered by the general principle of sincere cooperation, and (iii) of the Grimaldi doctrine, the duty to ‘comply or explain’, and other regulatory arrangements intended to improve the coherence, uniformity, and effectiveness of EU law implementation through soft law measures. Second, non-contractual liability will only arise in the case of manifest and particularly serious infringements. Yet what must be manifest and serious is not the breach of EU soft law – which is non-binding – but the breach of the relevant, indirectly triggered hard law rules or principles. Accordingly, a breach of equality or legitimate expectations must be manifest and severe for damages to be awarded. Finally, in cases of breach of the duties to take EU soft law into account and to give reasons for departing from its content, it will be extremely difficult to establish a direct causal link between the infringement of these duties – not the decision to disregard the soft law measure – and the damage suffered by the private party.

Under EU law, illegality is the only ground for compensation. In turn, the legal consequences of the principle of legitimate expectations at a national level can be more diverse. In particular, in some jurisdictions it may well be the case that the frustration of legitimate expectations by administrative authorities does not always lead to the annulment of administrative decisions, but only to compensation for damages – secondary protection. This shows that legitimate expectations would allow the design of a more refined and sophisticated system of remedies against inconsistent administrative conduct that the one provided by that EU law.

Punitive effects

EU soft law is not an appropriate instrument to create new sanctions in case individuals or entities do not comply with it, and therefore lacks external disciplinary effects. First, precisely because they are not legally binding, soft law measures cannot directly impose obligations or prohibitions on their addressees. Second, even if the substantive obligation or prohibition had been created by a hard law rule or decision, the principle of legality prevents soft law from establishing a criminal or an administrative sanction in case of infringement. Here, the requirement of foreseeability is incompatible with an act which is not intended to be binding.

In turn, soft law measures that convey internal administrative instructions under the principle of hierarchy may have internal disciplinary effects. Officials are obliged to implement them when making decisions, and in case of deviation they would violate the – certainly binding – duty of obedience imposed on them by the principle of hierarchy. Deviation from soft law measures triggers the principle of hierarchy, thereby instilling indirect internal binding effects. The peculiarity of these internal instructions is that breaching them does not give rise to external invalidating effects – their legal effects remain within the administrative organization. As far as EU law is concerned, the Staff Regulations give them internal punitive effects by providing that any failure by EU administrative officials to comply with their obligations, including the obligation to abide by hierarchical instructions and orders, whether intentionally or through negligence, shall render them liable to disciplinary action.

Conclusion

This analysis shows a more complex and multifaceted picture of the legal effects of EU soft law than the binary approach that emerges from the study of its legally binding nature. The conclusions drawn from it also allow us to identify the components with which the EU legislature and the Court of Justice can draw the scope and types of legal effects of EU soft law: conferring qualified interpretative effects to it; establishing different regulatory arrangements to foster compliance with soft law measures; extending indirect invalidating effects through hard law rules and general principles of law; awarding damages on ground of mere inconsistency; and exploring internal disciplinary effects are some of them.

—

Posted by Professor Luis Arroyo Jiménez (Jean Monnet Chair of European Administrative Law at UCLM; luis.arroyo[@]uclm.es)

Suggested citation: Luis Arroyo Jiménez, “Beyond ‘Bindingness’. A Typology of EU Soft Law legal Effects”, REALaw.blog, available at https://wp.me/pcQ0x2-Jz